Hell Gone Mad

We want to caution readers that there are some graphic descriptions of the events that may not be suitable for readers of all ages.

Michigan’s Men of the USS Indianapolis Disaster

Built by the New York Ship Building Corporation of Camden, NJ, the USS Indianapolis (CA-35) was a U.S. Navy Portland-class heavy cruiser commissioned into service between wars on November 15, 1932. She was initially armed with nine 8” 55 caliber guns and four 5” 25 caliber guns and had two catapults to launch four on-board float planes. Her general specs were 610’ 3-3/4” long and 66’-5/8” extreme breadth (beam). She had treaty displacement of 10,000 tons, 9,500 tons of standard displacement. The Indianapolis, affectionately known as the “Indy”, had a plant designed to develop 107,000 horsepower at 366 R.P.M. to attain 32.7 knots, meaning she moved briskly at almost 38 miles per hour. During later retro fits, one catapult was removed and 24 40-millimeter Bofors and 16 20-millimeter Oerlikon anti-aircraft guns were added among other period upgrades. She was so exceptional and state-of-the-art, she became the flagship of the Navy’s Fifth Fleet in the Pacific and hosted then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt. She spent most of her early peace time commission moving Roosevelt and other dignitaries around the Americas and performed other assigned duties, then returned to her home port of Long Beach, California. In September of 1939 at the beginning of World War II, her home port was changed to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

The Indianapolis missed the carnage December 7, 1941, as she was some 750 nautical miles away (about 863 miles) from Pearl at Johnston Atoll performing gunnery drills. Upon receiving the attack announcement, she immediately set off for her home base and faced no enemy encounters on the way. She arrived at Pearl Harbor December 13 and joined Task Force 11, with the carrier USS Lexington and her sizable air group; two other heavy cruisers, the USS Chicago and the USS Portland; seven destroyers; and the fleet oiler, Neosho.

Between February 1942 and September of 1944, the Indy engaged in various heroics in the Pacific Theater and was awarded eight of her eventual 10 Battle Stars.

CAPT Charles Butler McVay, III © Bettman/Getty Images

Charles Butler McVay, III was the tenth and final commander of the USS Indianapolis, a 1920 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and an esteemed career naval officer. He was born in Ephrata, Pennsylvania on August 31, 1898. His father was Admiral Charles Butler McVay II, the former commander of the Navy’s Asiatic Fleet in the early 1900s. Between duty assignments on 10 different vessels, McVay held various positions in the Navy Department. He assumed command of his first ship in 1935 and went on to command several others when not ordered back to Washington DC. From May 19, 1943, through October 18, 1944, he served as the Chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee of the Combined Chiefs-of-Staff in Washington. In this very high-level position, he would have had first-hand knowledge that America had penetrated Japan’s ULTRA naval code. One month later, the USS Indianapolis was his to command.

McVay’s new appointment as commanding officer of the ship was signed off on by Admiral Ernest King, Chief of Naval Operations. Although there are no records of any hesitation or issues King had with approving McVay, he proved to be a very influential factor in the remainder of McVay’s career and life.

CAPT McVay’s command of the Indianapolis was stellar. From the time he took over on November 18, 1944, the Indy participated in the Tokyo raids and invasion of Iwo Jima in February of 1945, and the bombing of Okinawa the following month. The latter action saw the crew shoot down seven enemy aircraft and a kamikaze pilot’s bomb slam through the deck of the ship, killing nine and injuring many more. Under McVay’s skillful maneuvering, the Indy managed to somehow limp all the way back to Mare Island Naval Shipyard in California to repair the extensive damage done to the ship’s hull by the bomb and subsequent flooding. For this final flurry of gallantry, the USS Indianapolis was awarded its prestigious 9th and 10th Battle Stars.

USS Indianapolis (CA-35) Off the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, 10 July 1945, after her final overhaul and repair of combat damage. © U.S. National Archives

After the repairs were completed at Mare, the ship moved to nearby Hunters Point Naval Station on July 16, 1945, where she was loaded with a top-secret cargo and took on two “military officers” who were, in actuality, American scientists. Only the two scientists knew what was in the mystery load guarded around the clock and why CAPT McVay was ordered to speed to the Mariana Islands’ Naval Base Tinian: they were carrying the firing mechanism and uranium used in the assembly of “Little Boy,” the atomic bomb targeted for Hiroshima. McVay departed Hunters Point that same day at 0800 hours with 30 new officers and 250 new enlisted men, most of whom were not yet combat trained; most were also very young.

The Indy sped from San Francisco to Pearl Harbor in just 74.5 hours. At Pearl, McVay refueled and received additional instructions for the continuation to Tinian with their precious cargo. They departed Pearl Harbor the same day, July 19, and sped onward to Naval Base Tinian arriving July 26, a record-breaking passage time that still stands. After unloading, McVay headed to Naval Base Guam, arrived July 27, and received instructions to sail to Leyte, Philippine Islands for the new men to undergo gunnery training at 1100 hours on July 31. The Indy departed Guam for Lehte very early the morning of the 28th as instructed. This is where the story turns.

No one had alerted CAPT McVay that decoded ULTRA chatter revealed four Japanese submarines patrolling the Philippine Sea and the Route Peddie he was about to travel. One of the subs had torpedoed and sunk the U.S. destroyer escort Underhill a few days earlier (July 24), but the vital information was inexplicably not conveyed to ex-intelligence officer McVay. As CINCPAC HQ (Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet headquarters) didn’t mention this, and McVay was advised in writing that “zigzagging” versus piloting a straight course was solely at his discretion, he chose not to. He was also not provided with an escort ship although one was later found to have been available. The lack of an escort and the omission of the integral ULTRA intel led to no sense of immediate danger and an extraordinarily deadly outcome.

A few minutes before midnight on Sunday, July 29th, one of the four Japanese subs, the I-58 commanded by Lieutenant Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto of the Japanese Imperial Navy, spotted the Indianapolis silhouetted against the moon when it peeked through the cloudy night. She was very close, only about five miles east of his position. The sub dove and its rather unremarkable captain sprang into action. Hashimoto himself loaded six of his forward torpedo tubes, fired each two seconds apart, and exploded into nautical infamy.

Minutes after midnight on Monday, July 30, 1945, the first torpedo ripped about 60 feet of the bow off the Indy, while the second hit machine rooms, a powder storeroom, and a fuel tank. Shortly after the fatal second hit there was no electrical power (lights, radios, or phones) to communicate inside or outside the ship, and no water pressure to fight the out-of-control fires. As explosions and numerous fires raged, the ship started to roll almost immediately. Taking on huge amounts of water and gushing fuel, the USS Indianapolis took only 12 minutes to sink 18,000 feet (3-1/2 miles) to the bottom of the Philippine Sea. Of the 1,195 total aboard, approximately 300 were still trapped inside when she went down. Not one of the Indy’s 28 African American crewmembers, aged 17 to 38 years old, survived. It is still the greatest loss of life from a single American vessel in United States Navy history.

This left almost 900 souls - many horribly burned or seriously injured - dumped into the water with few life rafts, life belts good for only a finite period, no provisions, and most completely covered in thick bunker oil (fuel). The explosions, floating corpses, blood, and flailing survivors at the scene drew oceanic whitetip and tiger sharks almost immediately.

The next four days in the water were pure hell. The thick bunker oil clung to their skin and was in their eyes, swelling them shut and infecting them. The water was very cold at night, but the merciless sun reflected hot and blinding off the water during the day. The salt water stung their many open sores and wounds, with many men suffering from having digits and limbs blown off.

The sea water was most problematic in that the men were extremely thirsty but could not drink it. The salt caused deadly hypernatremia: they drooled, vomited, and their tongues swelled. The high sodium content caused even further severe dehydration as it progressed to diarrhea and cramping as their kidneys started to shut down. There were numerous reports of the men mass hallucinating and “going mad” before sinking into a coma and dying, all within a short time after saltwater ingestion. If the delirious men swam away from the debris they were hanging on to or just tired and drown, the sharks grabbed them. Sharks also went for the injured or weakened men, the smell of blood and body parts attracting swarms to the bobbing men. Survivors spoke of warning delirious men to return to the floating groups and to stay clear of the dead bodies to lessen attacks. There were also reports of men speaking to each other while sharks suddenly descended on a hapless shipmate in the group, tearing at him, before dragging him under in a final feeding frenzy while they watched. A few survivors speculated that perhaps they were not targeted because of the thick bunker oil coating their extremities, making them less attractive bait than others to the sharks. Whatever the case, the hundreds of survivors in the water were winnowed down rapidly with each passing hour between injuries, dehydration, exposure, hypernatremia, and intentional suicide. By sunrise Wednesday, August 1, the number was estimated to be down to about 400 men still alive.

During later investigations it was discovered that there was no attempt by the military to determine why the USS Indianapolis did not make it to port in Leyte at 1100 hours on July 31 as ordered. Their absence was apparently overlooked or they were simply forgotten.

LT Wilbur C. Gwinn who first spotted the survivors. © USS Indianapolis Legacy Organization

On the morning of Thursday, August 2, there was finally some action. Navy pilot Lieutenant Wilbur C. Gwinn was leaning aft from his PV-1 Ventura repairing a broken antennae trailing his aircraft when he thought he spotted something that looked like a long oil slick. As were no reports of American ships in the area, he took his plane down low over the water suspecting it could be an enemy sub. At the closer distance he saw an unbelievable sight: quantities of men bobbing and waving frantically amid circling sharks in a debris field. He dropped a raft with emergency provisions down to the men, then got on the radio to his home base in Peleliu with the location and news of a major disaster with survivors. It took several messages with increasing quantities of men sighted before the base finally believed him and sprang into action for a rescue operation. Another Ventura pilot at the base, Lieutenant Commander George Atteberry announced he was relieving Gwinn and set off after hearing the radio chatter. Likewise did a nearby pilot in a Martin PBM long-range flying boat, who reached the area and dropped more rafts and circled the men to mark their location for others. By now about three hours had elapsed from when Gwinn first spotted the survivors.

Lieutenant Richard A. Marks and his Catalina “Dumbo” PBY flying boat was also dispatched to the scene. Marks conversed with a friend commanding a destroyer he was passing over on the way and described the rescue mission. The destroyer, the Cecil J. Doyle captained by Lieutenant Commander W. Graham Claytor, Jr., immediately set off for the site himself to assist. The destroyer arrived before the slower PBY did after 1600 hours. LCDR Atteberry “spotted” survivors for Marks, who then dropped several rafts filled with emergency supplies and whatever provisions he had on-hand. LT Marks decided to attempt to set down his PBY in the choppy water amid the men, a serious gamble and very much against military rules. The PBY sustained a bit of damage but made it safely onto the surface. After four and a half days in the Philippine Sea, the first survivors were pulled aboard the craft by Marks and his crew.

Once the PBY’s interior was completely filled with men, the crew lashed other survivors to the top of its long wings to lift them out of the water. LT Marks’ PBY was in very poor shape by this point and weighed down with rescued, very ill men and blood. The plane was ordered destroyed the following morning, August 3, after all survivors were safely offloaded onto other arriving vessels.

LCDR Claytor’s destroyer had arrived shortly after midnight and had begun the terrible task of retrieval and burial at sea of some of the bodies of the deceased who had not yet been taken by sharks. There were reports of men pulled out of the water with just the top half of their bodies still in their life belts, their lower half lost to sharks. Between the Cecil J. Doyle, the second PBY, a destroyer and its escort, and three fast transports, the remaining survivors were fished out and taken to Peleliu or Samar by late afternoon August 3. All told, 316 men were rescued including CAPT McVay. The last ships that converged on the disaster site performed final debris clean-up and body retrieval / burial at sea operations. Three of the 93 burials were Michigan men, with some 44 bodies recorded as “non-identifiable”. The recovery effort officially ended Thursday, August 9 after the water surface was completely scanned for 31,400 square miles looking for anything left behind. The only sign of the disaster now was the dissipating oil trail.

The purposeful decision was made at the highest level of government to disclose nothing about the USS Indianapolis until August 15, the date of the Japanese surrender to the U.S., ensuring the tragedy and its handling were not the top headline in the news.

The official inquiry into the disaster opened in Guam on August 13. The military seemed to be looking for a scapegoat or someone to “make an example of”, and they created one in the blameless CAPT McVay. They court-martialed him for “not giving the abandon ship order” – which his men readily testified he did – and for “hazarding his ship by failing to zigzag.” Many military experts were of the opinion that the charges should never not been brought in the first place. Besides the fact that McVay was told that zigzagging was discretionary, he was not told that there were four Japanese submarines in the area who had already torpedoed the Underhill. The decision to court-martial was very unpopular, especially with his surviving men.

LCDR Mochitsura Hashimoto testifying at McVay’s court-martial. © Corbis Historical/Getty

Another inexplicable wrinkle was added when then-Secretary of the Navy, James Forrestal and then-Chief of Naval Operations, ADM Ernest J. King brought in LCDR Hashimoto of the Japanese Imperial Navy to testify against McVay! It was absolutely unheard of for the United States to bring in literally “the enemy” to testify when trying the court-martial of an American military officer, but they did so. Prosecution witness Hashimoto expounded on exactly what the American officers and crew had already testified to: there was absolutely no way that the USS Indianapolis was not going to be hit at that close range by his torpedoes; the ship could have zigzagged all it wanted. Unmoved, the court-martial proceeded and McVay was convicted.

Although his sentence was unanimously, but quietly, remitted, and he was given a “tombstone promotion” to Rear Admiral upon his retirement a few years later, McVay’s stellar career and reputation was likewise torpedoed.

In the coming years, McVay attended Indy reunions and stayed in touch with his men, who still thought very highly of him. He never referred to himself as Rear Admiral, but as Captain. He wrote letters to every one of the families of the men who had perished in the disaster; was haunted by severe survivor’s guilt; and was ashamed of his court-martial and inability to command ships, which he loved. He also received hate mail and threats from families of the deceased for the remainder of his life. In 1968, at the age of 70, Charles B. McVay, III walked down the stairs of his home onto his lawn and shot himself in the head with his service pistol. Captain McVay is broadly considered the last victim of the U.S.S. Indianapolis disaster.

Over his exemplary career, McVay acquired the following meritorious medals according to his official Navy biography (7/13/1954): a Silver Star; a Purple Heart; a Bronze Star with combat “V,” for the assault on Okinawa; a Victory with fleet clasp; the Navy Expeditionary; the China Service; the American Defense Service with bronze “A”; the American Campaign; the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign with four bronze stars; and the World War II Victory. He didn’t live to see his Naval Unit Commendation or Congressional Gold Medal awarded.

Over the decades, McVay’s men, military peers, relatives, and other interested parties tried to clear his good name, including LCDR Hashimoto. The latter became a Shinto priest and sought forgiveness from the individual survivors for his part in the disaster while advocating for McVay until his own death in 2001.

Once Captain William Toti, retired commander of the USS Indianapolis (SSN-697) a Los Angeles-class submarine became involved, additional serious light was shown on McVay’s court martial and why it shouldn’t have been allowed to happen. He worked diligently from 1998 - 2001 to publicly clear McVay’s reputation. Toti explained, “What I did do was analyze the attack from a submariner's perspective, assuming the Indy had been zigzagging. What I was able to demonstrate through submarine torpedo computer analysis that did not exist in 1945 is that even if the Indy had been zigzagging, it still would have been hit by one or more torpedoes. If that analysis had been possible during McVay's court martial, there is no way he would've been convicted.” What Hashimoto testified to at the court martial back in 1945 was proven by hard technical facts by Toti decades later.

Hunter Scott’s National History Day Indy project. © Pensacola News Journal

Running almost concurrently to Toti’s and Hashimoto’s actions, in 1997 a remarkable 12-year-old student in Florida, Hunter Scott, decided to do his middle school project for National History Day about the Indy after seeing the film Jaws. Unable to find much information in libraries, Scott researched the tragedy himself by contacting over 100 survivors for interviews and examined over 800 documents. What he discovered led him to also strongly believe in McVay’s innocence. As word of his project leaked out, he appeared on several television shows including “The Late Show with David Letterman.” Scott joined forces with like-minded members of the USS Indianapolis (CA-35) Survivors Organization to testify before the Senate Armed Forces Committee with his evidence in September of 1999. Congress reopened the court-martial case and exonerated CAPT McVay posthumously. Then-Representative Joe Scarborough (now of MSNBC’s “Morning Joe”) introduced legislation in October of 2000 to award the Naval Unit Commendation medal for “outstanding heroism in action against the enemy” to the Indianapolis’ final crew, which then-President Bill Clinton also signed off on. In May 2001, CAPT Toti, by then in Naval Operations at the Pentagon, ensured that the signed exoneration was physically placed in McVay’s service records to correct the decades-long injustice. CAPT McVay’s young “student savior” is currently Naval CNDR Hunter A. Scott, Executive Officer of Consolidated Brig Miramar, the military prison at California’s Marine Corps Air Station Miramar.

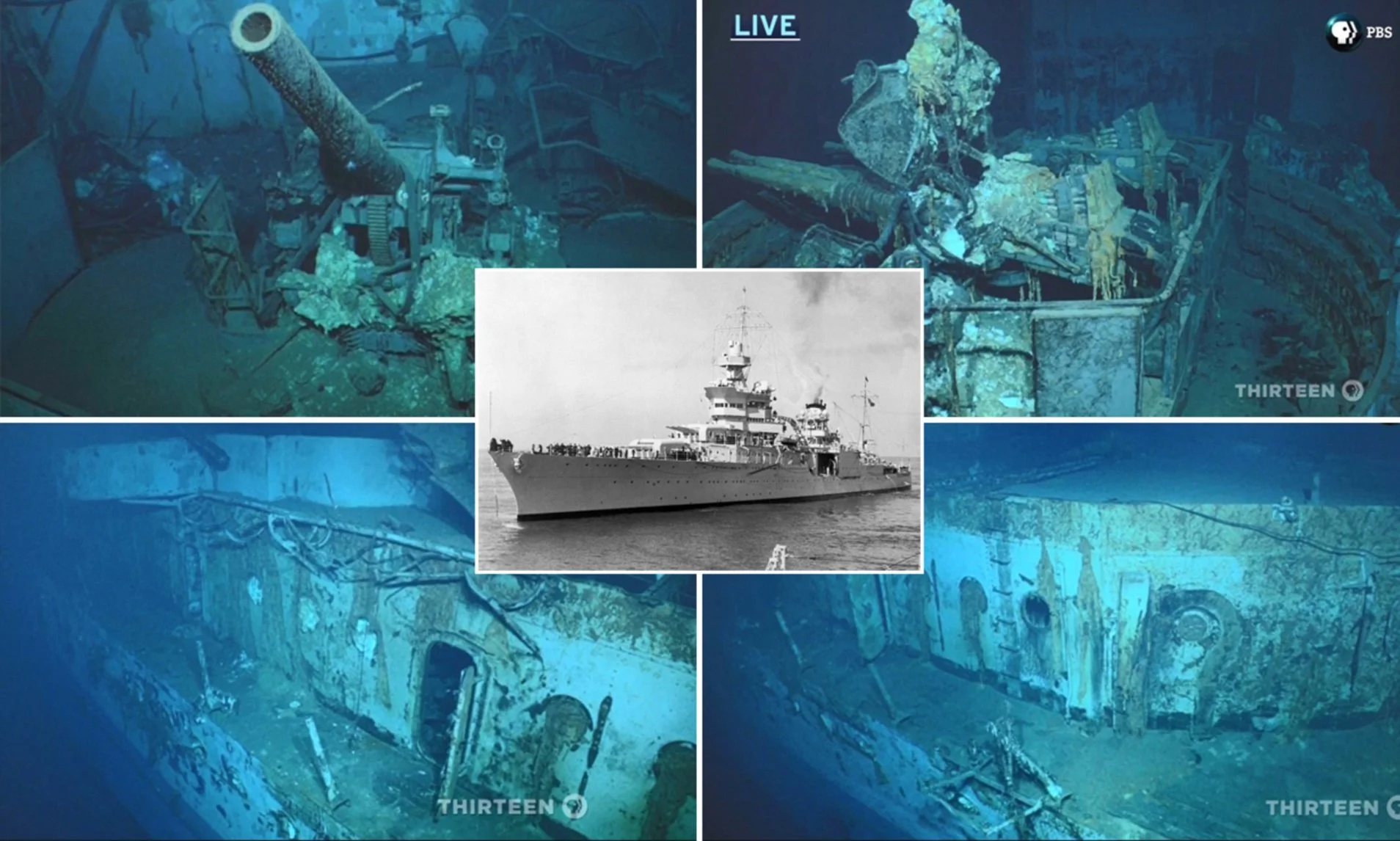

Part of the Indy’s hull revealing her number, 35. © PBS

On August 19, 2017, the wreck of the USS Indianapolis was discovered by R/V Petrel, a research vessel owned by entrepreneur / philanthropist Paul G. Allen and manned by a crew of 13 civilian researchers. They searched a wide radius a bit west of the original area where the Indy was thought to have sunk, 134 degrees 48’ East longitude, 12 degrees 2’ North latitude and hit pay dirt. The area was fully surveyed and documented, supplying many outstanding photographs and video footage. As the USS Indianapolis remains property of the U.S. Navy, and the sunken ship is an honored war grave, the exact location is confidential, and the site cannot be disturbed. For the survivors and victims’ families, it was a small measure of closure to see the ship again that disappeared so quickly 72 years earlier.

Montage of discovered Indy wreckage. © PBS

The lone Michigan survivor, S2c Harold John Bray, Jr. © USS Indianapolis Legacy Organization

Michigan, with 72, accounted for the state with the most young men and boys who were lost in the Indianapolis disaster. The victims were spread out from around the state, but there were a good amount from the Detroit area. 22 were from Detroit proper; two each from Flint, Highland Park, and Van Dyke (now known as Warren); and one each from Clawson, Inkster, Lincoln Park, Monroe, Mt. Clemens, Northville, and Royal Oak.

The lone Michigan survivor from the USS Indianapolis disaster, S2c Harold John Bray, Jr. was originally from Ramsey, Michigan but has lived in Benecia, California for many years. He enlisted at age 17 and was 18 years old at the time of the sinking.

Our Detroit area men lost:

S2 Lester James Ayotte, 18, Detroit

S2 Joseph Carl Beuschlein, 18, Mt. Clemens

S2 John Brake, Jr., 18, Detroit

BUG1 William George Cairo, 19, Detroit

S1 Delbert Elmer Dufraine, 31, Clawson

S1 William Harrison Casto, 26, Monroe

S2 Willard James Copeland, 19, Van Dyke

LT Ernest Stanley Goeckel, 23, Royal Oak

S2 Francis Joseph Patrick Kenny, 18, Detroit

SK3 Thiel Joseph Klein, 24, Detroit

SM3 Ceslaus Chester Kolakowski, 19, Detroit

S2 Alfred Meciuston Kusiak, 17, Detroit

S2 Solomon Latzer, 26, Detroit

S2 Raymond Irving Livermore, 18, Detroit

S2 Edward Richard Lorenc, 17, Detroit

S1 LaVoice Mansker, 17, Detroit

EM2 David Leroy McClure, 30, Flint

S1 George Edward McKee, 19, Detroit

S2 Manual Angel Mencheff, 16, Lincoln Park

GM3 Robert Bruce Monks, 17, Highland Park

F2 John Hubert Niskanen, 18, Highland Park

S2 William Gerald Nugent, 17, Detroit

Y3 Orlando Robert Ortiz, 20, Detroit

S2 Robert J Perry, 18, Flint

S2 Donald Martin Pokryfka, 17, Detroit

S2 Raymond Lee Poynter, 17, Detroit

S2 Walter Matthew Prior, 17, Detroit

S2 William Charles Puckett, 17, Van Dyke

S2 Jesse Edmund Reese, 17, Detroit

F1 Vernon Lee Rhodes, 26, Detroit

S2 Charles Walter Roof, 17, Detroit

F1 Henry August Smith, 19, Detroit

S2 William Carl Solomon, Jr., 17, Inkster

S2 Archie Joseph Stankowski, 18, Detroit

S2 Robert Louis Stueckle, 17, Northville

The remaining young men from Michigan who perished in the USS Indianapolis disaster:

Battle Creek: S2 Richard Eugene King, 18 and S2 Lawrence Edward LaParl, 18

Bay City: F1 Clifford Carson, 27 and S2 Donald Frorath, 18

Byron: S2 Edwin Lee Smith, 18

Charlotte: S2 John Nelson Dimond, 19

Coldwater: S2 Harry Leroy Amby Carr, 18

Croswell: F2 Thomas McNabb, Jr., 18

Douglas: F2 Steve J. Magdics, Jr., 18

Fruitport: S1 Theodore Francis Miskowiec, 34

Gaylord: S2 Loris Eldon Sewell, 18

Grand Rapids: S2 Kenneth Jay Beukema, 18; S2 Ralph Engelsman, 29; COX Paul Edward Knoll, 21; S2 Robert Walker LeBaron, 17; S1 Charles Marciulaitis, 31; and S2 George David Payne, 17

Grant: S2 James Patrick Sullivan, 17

Jackson: S2 Charles Lee Myers, Jr., 25

Kalamazoo: S2 Richard Eugene Drury, 17

Lansing: WT2 Walter Herman Selbach, 23; S2 Robert Carl Strieter, 18

Leslie: S2 Lewis E. Morgan, 18

Marysville: S2 Charles Calvin Moulton, 19

Mendon: S2 Walter Raymond Miller, 17

Midland: F2 James Joseph Drummond, 25

Owosso: S2 Maynard Lee Humphrey, 17

Saginaw: S2 William Theo Praay, 18

South Haven: S2 Jerome Richard Suhr, 17

Three Rivers: S2 Dale Eugene Stone, 18

Wheeler: S2 Wilbur Melvin Bott, 18

The original plaque for the Michigan men.

On July 30, 1946, on the first anniversary of the disaster, a large bronze plaque memorializing the 72 Michiganders of the USS Indianapolis sinking was presented at the old Veterans Building to Detroit Naval Post No. 233, Veterans of Foreign Wars in a solemn ceremony. The plaque read: “In Loving Memory of Our Boys from the State of Michigan Who Gave Their Lives with the Sinking of the USS Indianapolis July 30, 1945”; it was given “By Their Families.” The plaque was created by the Parents Plaque Society and presented by its chairman, Charles Roof, to CAPT Hubert Lemon, the post commander. Post 233 was the official guardian of the memorial until the new Detroit Civic Center was built and a new permanent place for its installation there was determined. The Detroit Free Press reported that Arthur Greig, Michigan commander of the VFW, and former Navy chaplain, Rev. T. Williamson addressed the post members and the parents of the lost men, and an illustrated history of the ship was prepared by the Navy and distributed at the event.

The original location the plaque was installed in, the first Veterans Building, was the famous edifice which had previously housed the Detroit Museum of Art at 704 E. Jefferson Avenue (at Hastings). Whether it moved to the new Veterans Administration Building when it opened in 1950, another building in the new Civic Center, or stayed in its original location until the old Veterans Building demolition in 1960 is unknown at this time. We only know that it disappeared for decades, much to the disappointment of the victims’ families, USS Indianapolis enthusiasts, and those that had only heard rumor of its existence.

A casual inquiry to Detroit Historical Museum curator Bill Pringle asking if he had it in the organization’s huge collection resulted in him locating it a few months later. It had apparently been taken in years ago when the Detroit Historical Museum was run by the City of Detroit and had not been recorded. The curation team thoroughly cleaned the plaque, then pledged to restore it immediately to public viewing.

On Sunday, August 17, at 1pm, the USS Indianapolis plaque will be unveiled in the Detroit Historical Museum’s Arsenal of Democracy where it will remain on permanent display. At 2pm, Jeff Ortiz, nephew of Y3 Orlando Robert “Bobby” Ortiz and Ralph McNabb, nephew of F2 Thomas McNabb, Jr. will present a comprehensive lecture about the ship and its lost men. Both speakers are members of the USS Indianapolis Legacy Organization, who work tirelessly to uncover new facts and materials surrounding the disaster and its crew. Some of the other victims’ family members will also be on hand for the unveiling.

Although we have studied the disaster and dissected the various actions of the main players involved for 80 years now, one still can’t really comprehend what the crew of the USS Indianapolis went through during their 4-1/2-days in the water and how it impacted the rest of the survivors’ lives. 20-year-old Rhode Island survivor, SM3 Frank J. Centazzo described their truly horrifying ordeal as “hell gone mad.”

The survivors aboard the Hollandia returning to the U.S. © IndyStar.com

Suggested additional resources:

The Detroit Historical Society’s unveiling and lecture event.

USS Indianapolis Legacy Organization

USS Indianapolis (CA-35) by Philip A. St. John, Ph.D. (Turner Publishing). A great fact-packed primer for all ages, with lots of photos, route plotting, and crew detail.

Indianapolis: The True Story of the Worst Sea Disaster in U.S. Naval History and the Fifty-Year Fight to Exonerate an Innocent Man by Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic (Simon & Schuster). The meticulously researched and written New York Times bestseller documents the disaster.

Video footage of the R/V Petrel discovering and exploring the Indy.

Special thanks to: Jeff Ortiz and Ralph McNabb, USS Indianapolis Legacy Organization; Bill Pringle and Tracy Irwin, Detroit Historical Museum; William Toti, former commander of the USS Indianapolis (SSN-697); Richard Hulver, Ph.D., Naval History and Heritage Command; US National Archives; Defense.gov; navsource.net; Smithsonian Magazine; Indystar.com; Project888; Detroit Free Press; DailyJaws.com.