THE GREAT JANUARY PASSINGS

by Betsy Alexander

Reader’s note:

The Alger family includes several generations of men named Russell. For clarity throughout this story:

Russell refers to the father of General Russell Alexander Alger

General Russell Alexander Alger (Russell Sr.) refers to the Civil War general and public servant

Russell Alexander Alger Jr. (Russell Jr.) refers to his son

The two most prominent of the (several) Russell Alexander Alger’s, specifically the former statesman/lumber baron General Russell Alexander Alger, and his son the capitalist/“The Moorings” owner Russell Alexander Alger, Jr., also shared one tragic commonality: both father and son passed away in late January, on the 24th and the 26th to be exact.

Born on February 27, 1836, in a log cabin, Russell Sr. was raised in humble circumstances on a small plot of farmland in rural Lafayette Township, Medina County, Ohio. The Alger family consisted of father Russell, mother Caroline (Moulton), and four children. Russell Sr. was the second eldest of the siblings, with two sisters, Ann and Sybil, and a younger brother, Charles.

According to contemporaneous accounts published in the Medina County Gazette, Russell, the father of General Russell Alexander Alger, was described as a volatile and unreliable husband and father who struggled to maintain steady work, ultimately losing the family farm and cycling through a series of jobs. Newspaper reports from the time comment on his difficult temperament and its effect on his business prospects and relationships with co-workers, neighbors, and family.

One account recounts an incident in which he reportedly stood by as young Russell Sr. nearly drowned in a stream, intervening only after onlookers urged him to act. Other local accounts note that it was the frail young Russell Sr., rather than his father, who regularly walked nine miles each way to the grist mill to provide grain for the family.

Caroline Alger was reportedly the opposite of her husband, described in Medina County Gazette newspaper files as “bright, good-looking, and cheerful by nature.” It is also noted that “she tried to instill high character in her children” in spite of their turbulent home life. The unhappy couple finally split up, and their four young children were separated, passed around between relatives and whomever would help them.

By early 1851, Caroline, her husband Russell, and their daughter Ann had all passed away, leaving the three remaining children dispersed among relatives and others willing to care for them. As the eldest surviving child, young Russell Sr. was left largely to fend for himself while also assuming responsibility for his younger brother and sister. He secured room and board, clothing, schooling, and other necessities by working on farms and assisting at a local school, gradually moving from bartering for goods to earning wages. He eventually put himself through school, passed the bar, and by 1859 was working at a law firm near Cleveland. On December 31, 1860, he moved to Grand Rapids, Michigan, where he practiced law to support himself while seeking more outdoor-oriented work.

Despite his early hardscrabble upbringing, Russell Sr. developed a reputation from childhood onward as being loyal, responsible, notably kind, and remarkably honest. While living in Grand Rapids, he met Annette Henry, and the two were married on April 2, 1861. She may have been less than thrilled four months later when he announced he had enlisted in the Union at the outset of the Civil War (August 26). Before departing, he asked her oversee a small investment he had made in a lumber concern and use her best judgment while he was away. She apparently did so successfully, as his investment made money during his absence.

Russell Sr. assembled his own group of enthusiastic fighting men who became Company C of the Second Michigan Volunteer Cavalry. Easily distinguished as a natural soldier, he mustered in on September 2, 1861, at the rank of captain and led his own company.

He was promoted to major on April 2, 1862, and was nearly killed a short time later during a fierce battle charge when he was thrown from his horse, his side crushed and five ribs broken. On July 1, 1862, he was again wounded and taken prisoner at Booneville, escaped the same day, and returned to battle after recovery.

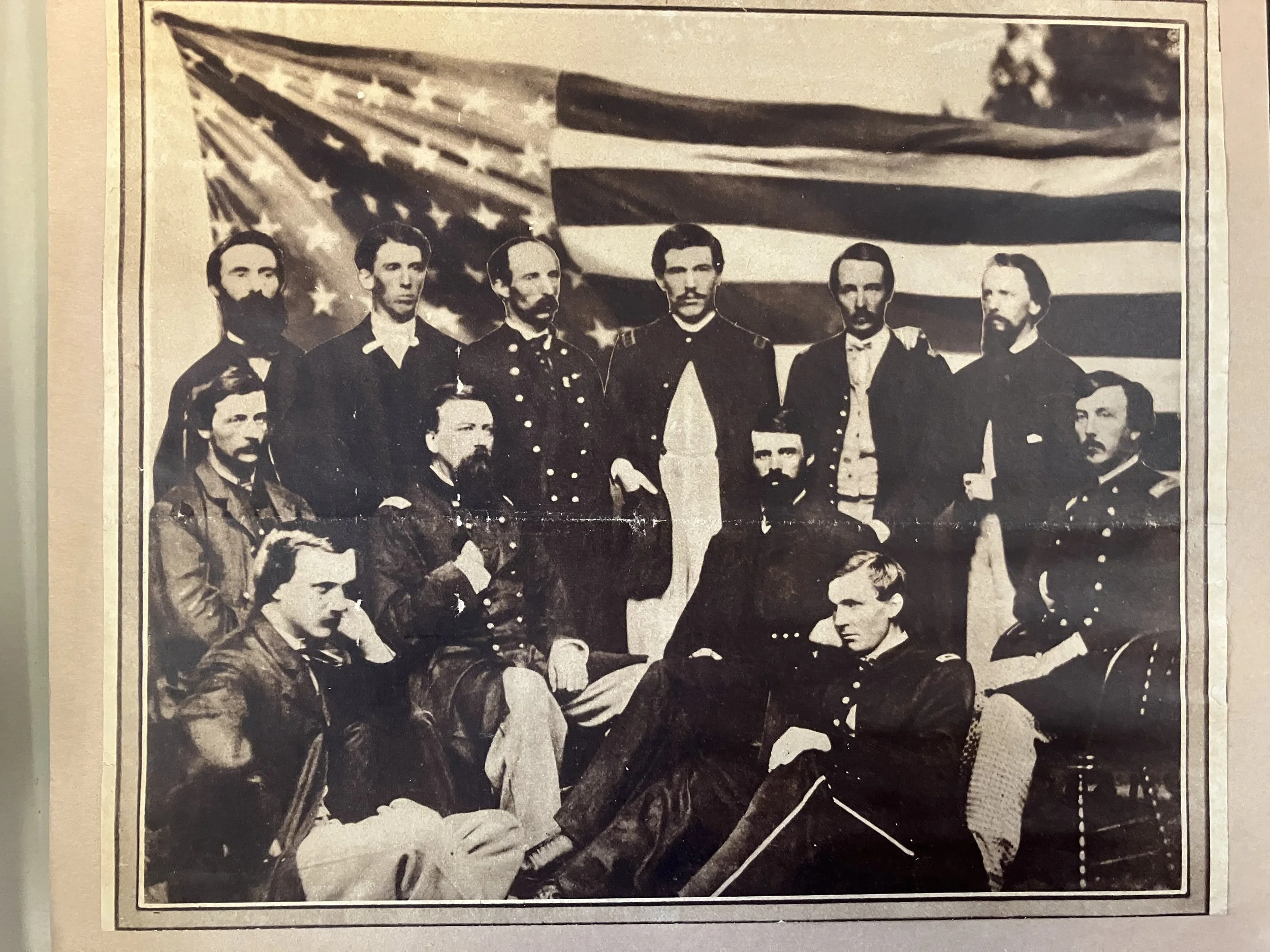

Col. RA Alger (center) surrounded by a portion of his staff

Russell Sr. was elevated to lieutenant colonel of the Sixth Michigan Volunteer Cavalry on October 16, 1862, and made colonel of the Fifth Michigan directly under General George A. Custer on February 28, 1863.

While with the Fifth, he fought in several key battles of the Civil War—Boonsboro, Trevillian Station, and Gettysburg, the latter where he personally led the first Union regiment into the town for battle. He was severely wounded again at Boonsboro on July 8, 1863, and finally retired on September 20, 1864, at the rank of colonel.

Russell Sr. was designated brevet brigadier general for his actions at Trevillian Station, then promoted again by President Andrew Johnson to brevet major general a year later for his “gallant and meritorious services during the war”. As General Alger, he went on to fight in 66 Civil War battles and skirmishes and served as President Abraham Lincoln’s envoy on special assignments when not engaged in battle or hospitalized. He was highly commended by his superiors and peers, including General Henry Halleck, General George McClellan, General George Custer, and Colonel Philip Sheridan, and was widely regarded by contemporaries as an effective military strategist.

The Algers moved to Detroit in 1865 to pursue business opportunities for General Alger. He first worked for a shipping firm in 1866, then decided that concentrating on the lumber industry remained the most viable path, as lumber was essential to postwar rebuilding. He acquired sizable swaths of wooded acreage in northern Michigan, which became the Manistique Lumber Company, later Alger, Smith & Co. He then created the Detroit, Bay City, and Alpena Railroad, a light rail line built to transport his timber, and purchased a shipping line for the same purpose. He acquired extensive pine holdings around Lake Huron; into Canada as far as Quebec; around Puget Sound, Washington; in Alabama; and across large portions of northern Florida. In addition to timber, shipping, and light rail, he amassed wide-reaching North American interests in banking, oil, mining, and livestock. He was also a director of several significant Michigan business enterprises, including Detroit National Bank, State Savings Bank, Peninsular Car Company, and Detroit Brass and Rolling Company. His business ventures were consistently successful, and his employees demonstrated notable loyalty to him, much as his troops had during the war.

Throughout his lifetime, General Alger never lost sight of who he was and where he came from. He went on to become Michigan’s governor, a two-time Michigan senator, and U.S. secretary of war. General Alger’s longstanding involvement with the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) culminated in his election as national commander-in-chief of the GAR from 1889 to 1890. He was an early member of the Massachusetts Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), an even older Civil War veterans’ organization founded in 1865, and co-founded the Michigan MOLLUS Commandery. It was this organization that organized the installation of the Russell A. Alger Memorial Fountain in Detroit’s Grand Circus Park.

On January 24, 1907, after greeting Annette, he advised he was feeling unwell and returned to his bed. He died shortly thereafter at 8:45am with his wife and son, Fred at his side; the coroner’s cause of death was “acute edema of the lungs.” Always fragile, General Alger had not been in good health for many years due to chronic heart valve issues and residual damage from the severe injuries sustained during the Civil War.

Although he had requested a simple funeral in keeping with his low-key demeanor, he ended up with two “state-type” funerals: one in Washington, DC where he passed and one in Detroit which saw an enormous number of grieving admirers. Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Truman H. Newberry, made all of the arrangements as Fred and Annette Alger were too bereaved. Eldest son Russell Jr., who would have traditionally made the arrangements, was somewhere between Florida and Cuba on his yacht and was yet to be located.

Since General Alger died while an extremely popular sitting senator, President Roosevelt, Vice President Fairbanks, Chief Justice Fuller of the Supreme Court, and scores of cabinet members, ambassadors, and other District dignitaries packed the service held at his Sixteenth Street residence and the prior public viewing. Former Confederate officers who had fought against General Alger sent large sprays of violets tied up with gray and blue ribbons and notes of sympathy to his widow, an unbelievable sign of great respect. Per the New York Times (1/27/1907), his remains were then loaded onto the Edgemere, one of six private railcars, along with the entire Alger family and a cadre of Congressmen and headed to Michigan following the Washington ceremonies.

The funeral train arrived in Detroit the following morning, Sunday, January 27, to collect additional dignitaries. Although it arrived nearly three hours late, it reached the city in time for the public viewing scheduled to begin promptly at 2:00 p.m. Four lines of mourners streamed continuously past General Alger’s solid mahogany casket at Detroit City Hall during the three-hour viewing that afternoon. The hall’s interior was entirely draped in black, save for the American flag upon his casket and a single funeral wreath. Four U.S. soldiers stood at attention guarding him, with two police officers stationed at either end. Members of the United Spanish War Veterans of America served as active pallbearers for the viewing. A private service for family members and invited dignitaries was held later that evening at the Alger family’s West Fort Street mansion.

At General Alger’s funeral the following day, the active pallbearers were prominent Detroiters and Grosse Pointers: Henry B. Joy, Richard P. Joy, Sidney T. Miller, Colonel Stephen Seyburn, Strathearn Hendrie, Judge Henry A. Mandell, Cyrus E. Lathrop, and Howard G. Meredith. Detroit Mayor William B. Thompson ordered all flags flown at half-mast and directed that “all public buildings and schools be closed at noon, and merchants suspend all business during the funeral.” As a result, much of the city of Detroit came to a standstill that Monday as a mark of respect.

The Detroit Free Press (January 27, 1907) reported that the lengthy funeral cortege included 86 honorary pallbearers; members of a joint committee of the national House and Senate; state and national dignitaries; three full bands; forty mounted police officers; members of the Corinthians’ and other Michigan Freemason groups; representatives from 15 military organizations, including the Grand Army of the Republic and the Loyal Legion; and state, federal, and county officials. Bringing up the rear were hundreds of members and former members of the Newsboys’ Association, followed by the general public, as the procession moved solemnly from West Fort Street to Elmwood Cemetery in the bitter late January cold. General Russell Alexander Alger—philanthropist, businessman, statesman, and soldier—was laid to rest in vault no. 6 of the Alger mausoleum.

Russell Alexander Alger, Jr. was born February 12, 1873, at the stately Alger mansion on West Fort Street in Detroit. As the eldest surviving son of Annette and General Alger, he assumed responsibility at an early age for overseeing his father’s extensive business holdings and handled most of the associated travel, while his father tended to his political career in Washington. Russell Jr. was the only one of all of the Alger sons, specifically the direct male descendants of General Alger, who did not serve in the military.

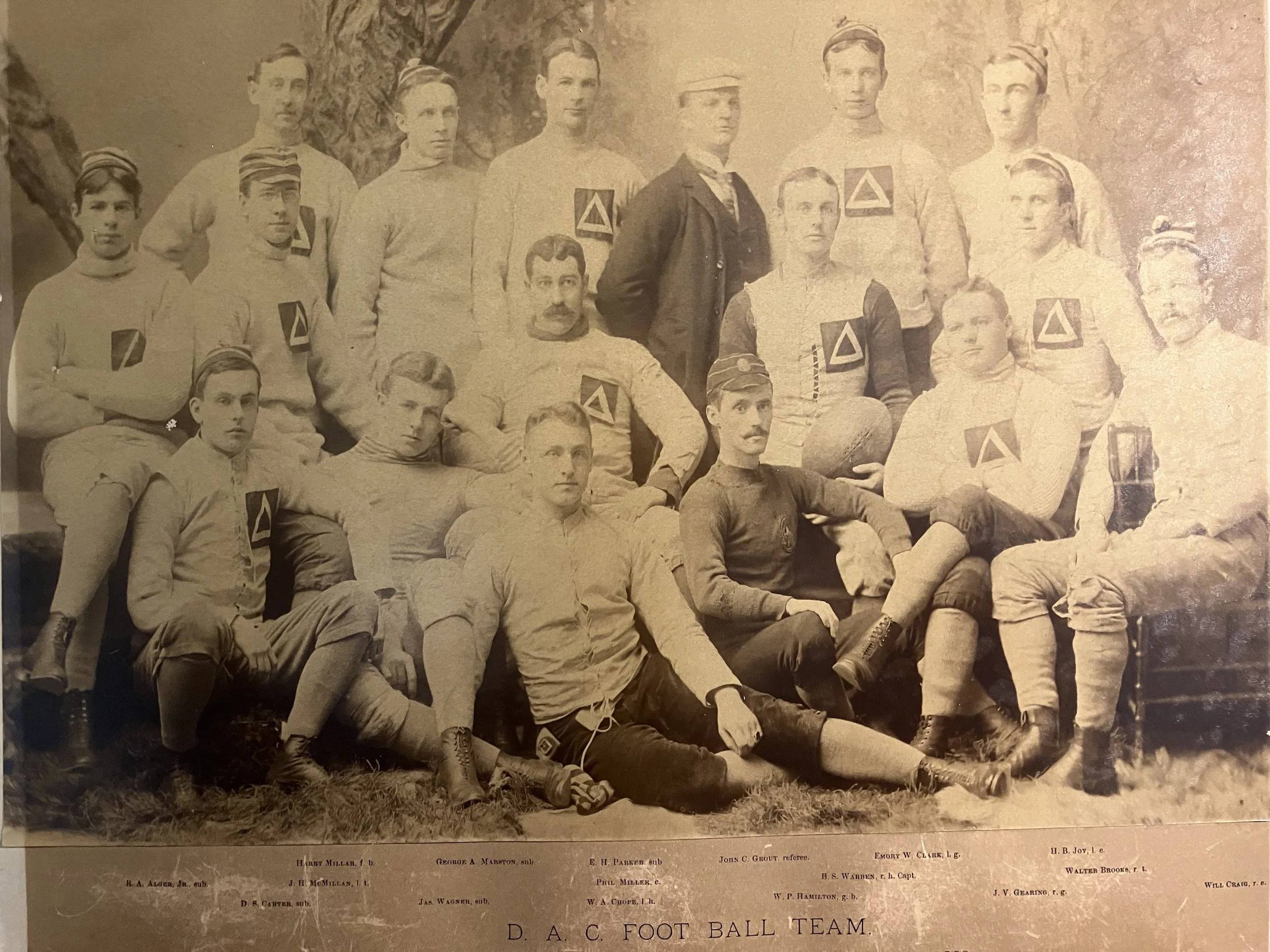

Young Russell A. Alger, Jr. (far left) and his Detroit Athletic Club teammates

Known as “Rusty,” Russell Jr. was an extremely robust and athletic young man, reportedly “built like a boxer,” compared to his father’s tenuous, lanky build. He excelled at nearly every sport he pursued, particularly football, golf, shooting, and a wide range of equestrian and water-based activities. If there was serious competition involved, even better yet; in all things, he played to win.

Russell Jr. also inherited his father’s savvy dealmaking and vision. A self-described capitalist, his ground floor investments in speculative new ventures soon reaped riches. He was able to ferret out new projects or products that would prove important in the near future. His ability to quickly and accurately grasp new projects’ intricacies then make sound detailed suggestions astonished his peers.

In addition to handling his father’s enviable business portfolio, Russell Jr. invested heavily in many of those enterprises while also pursuing his own major projects. In 1902, he became a leading investor in Henry B. Joy’s new automobile venture. Although several wealthy Grosse Pointers initially contributed capital, Henry and Russell Jr. were the ones to fully realize the new automobile’s potential. They worked closely with the company’s engineer making numerous refinements, and helped shape the business’s operational strategy. They relocated the Ohio Automobile Company from Warren, Ohio to Detroit and renamed it the Packard Motor Car Company honoring its founding brothers. Co-founder James Packard remained with the company as president, with Russell Jr. serving as vice president. Henry B. Joy later assumed leadership of the firm and remained with it into the mid-1920s, while Russell Jr. continued as an active member of the Packard Board of Directors until his death. The move to Detroit, the building of the famed Packard plant by Albert Kahn, and establishment of Packard cars as the top Detroit-manufactured car for discerning men of wealth and distinction all happened under their stewardship.

In 1909, Fred Alger and Russell Jr. became enthralled with what they believed to be another venture with large-scale potential: the Wright brothers’ aeroplanes. Intrigued by both the product evolution and its commercial promise, they wrote to Wilbur and Orville Wright several times before they finally agreed to a meeting in Detroit. The Algers brought the brothers to the Packard plant to illustrate how their planes might eventually be manufactured at scale and discussed broader business strategy. After gaining the Wrights’ confidence, Russell Jr. established Wright Brothers, Inc. alongside his friends Augustus Belmont and Cornelius Vanderbilt III. The powerhouse financial trio fended off patent threats and pursued infringement cases which allowed the Wrights to focus on aircraft development rather than litigation, which had been a major complaint of theirs.

From June 19 to 21, 1911, Russell Jr.’s Aero Club of Michigan sponsored the historic three-day Aviation Meet at the Golf Links of the Country Club, held on what is now Grosse Pointe South High School’s athletic field. This was an opportunity for media and the public to see a Wright Brothers Model B plane up close and, for the well-heeled, pay $25 (about $863 in 2026 dollars) for a quick flight over Grosse Pointe. The first passenger on the morning of June 19 was Russell Jr.’s eldest daughter and resident daredevil, fourteen-year-old Josephine Alger, who set the historical record as the first child (non-adult) in flight. The event was a sensation, and afterward the Model B was brought back to Russell Jr.’s home. Over the next several months, the Alger brothers and Wright pilot Frank Coffyn made many refinements, including the addition of pontoons, unofficially making it the first Wright seaplane. It was lashed to one of the four mooring poles on Lake St. Clair in front of the Alger villa when the brothers were not flying it back and forth to Canada or zipping over the Detroit River.

In 1915, after selling back their interests in the Wright Brothers, Inc., Fred Alger and Russell Jr. invested in the nascent General Aeroplane Company, the first to build aircraft in Detroit. Although there was an important military commission and enthusiasm for potential wartime use, the company dissolved in 1918.

Russell Jr. was extremely busy serving on the boards of some thirty companies, while pursuing new investments, and managing his father’s current business holdings. He traveled, competed in sporting events, and customized his various motorized “toys.” There was always something that could be dabbled in, experienced, won, or made to go faster. Life during the post-Edwardian era along the Grosse Pointe waterfront was superb, and the Alger’s had the millions during the heady days of the 1910’s approaching the Roaring Twenties to thoroughly enjoy it to the fullest.

Tragedy struck suddenly in 1921 when Russell Jr. was paralyzed following an accident at the Grosse Pointe Hunt Club. After being thrown from his horse twice, he was left permanently wheelchair-bound. The remainder of his life and his health suffered, just as his father’s had following his war adventures. He resigned from most of the boards he had been on and ceased most business activities. His main source of diversion was the yachting excursions or road trips his wife, Marion organized for them. Although, they maintained additional homes in Florida and Maine and traveled by ocean liners to places their yacht, Winchester could not, Russell Jr. remained completely dependent on Marion’s constant care.

Russell Jr. suffered a series of small strokes and other maladies before a massive paralytic stroke on December 7, 1928, while yachting off the coast of Havana, Cuba. He was taken to St. Luke’s Hospital in New York City, where he later suffered an appendicitis attack exactly one month later. After he was finally released his health was stable enough to again enable him to travel and make some social appearances throughout the remainder of 1929.

In mid-January 1930, Russell Jr. quietly returned to St. Luke's to receive what was intended to be corrective surgery for his stroke-related paralysis. He came through the surgery safely but developed pneumonia post-procedure and died in the hospital at the age of 56 on January 26, 1930.

Russell Jr.’s body was returned to Grosse Pointe from Manhattan and lay in repose at “The Moorings”. His funeral service commenced at 2:30pm on Wednesday, January 29, 1930, with his family and a multitude of friends and business associates in attendance.

That same day, The Detroit Free Press (1/29/1930) listed “more than 100 honorary pallbearers” for Russell Jr.’s funeral naming many prominent local families: Barbour, Bodman, Buhl, Dyer, Ford, Hendrie, Jennings, Joy, Ledyard, Lodge, McMillan, Macauley, Moran, Newberry, Seyburn, Sales, and Trowbridge; as well as Orville Wright. Unlike the funerals of his father, and later his brother Fred, the mourners did not march ceremoniously from his service at “The Moorings” down to Elmwood Cemetery. Instead, he had a traditional automobile funeral procession and was entombed in the Alger mausoleum in vault no. 3 directly, and appropriately, beneath his father.

When Russell Jr.’s will was probated the following month, it was disclosed that he left only about $2,000,000 (in 2026 dollars). This sum was likely significantly less than he’d originally had due to a combination of new income and inheritance taxes enacted after his father’s death, his own withdrawal from active business pursuits after 1921, and the catastrophic effects of the Wall Street crash of October 1929. Thousands of banks and businesses failed, stocks were meaningless paper, and millions of Americans’ life savings were completely wiped out. Despite these losses, Marion Alger appears to have remained on stable financial footing following the final settlement of his estate.

During their lifetimes, father and son attained great wealth, earned wide respect in Michigan, and, through their actions and business acumen, rose to national recognition and fame. Together, their influence extended across industries, institutions, and ideas larger than themselves, leaving a legacy that benefited the public and helped shape American history.

Sources & References

This post draws on a range of primary and secondary historical sources, including:

Medina County Gazette (1903 retrospective coverage drawing on earlier contemporaneous reports regarding Russell A. Alger’s early upbringing)

Detroit Free Press, January 27, 1907; January 29, 1930

New York Times, January 27, 1907

U.S. Civil War military records for General Russell A. Alger

Military correspondence and reports from the Civil War period

Detroit Historical Society collections and archival materials