HERE COMES SANTA CLAUS!

Way back in December of 1886, General Russell A. Alger decided to do something about all of the kids he passed on street corners literally freezing in the cold Detroit winters. They were poor newsboys, children and teenagers trying to bring in some money by selling newspapers for their starving families. Alger observed they didn’t have proper clothing - let alone winter attire - and had no prospects for obtaining new clothes. They were too busy hustling in the cold trying to contribute to putting food on their tables at home.

The General had also grown-up dirt poor in rural Ohio, orphaned at age 12 in the late 1840’s. He knew what it was like to have no food or clothing, and to be responsible for bringing in money to feed his younger siblings under miserable circumstances. He didn’t want other children to experience what he had growing up.

Alger tasked his personal secretary, J.C. McCaul, with doing some secret investigative work: he was to locate and vet “1,000 deserving families” who were impoverished and in dire need of assistance for survival. To these nominated families Alger would quietly deliver either a ton of coal or a cord of wood, depending on their specific heating need. He would also deliver one large barrel of flour so they could prepare food with this valuable grocery staple. McCaul was to ensure that the recipients on the city’s Poor Commission list knew nothing about their impending good fortune and he did not want the families embarrassed by their inclusion, if possible.

The second part of McCaul’s directive was to take every boy who belonged to the newly founded (1885) Detroit Newsboys’ Association and outfit them with a complete set of new winter clothes. The assembled boys were taken in groups of 100 to Detroit retailers Mabley & Company and J.L. Hudson to be measured then fitted out with new shoes, coats, hats, gloves, underwear, and warm woolen garments. This noisy and somewhat amusing process went on for several days at the two stores, with excited boys emerging resplendent in their new winter wardrobes.

This was such a success and a boon to the community, that it quickly became an annual Alger tradition. By the following year, McCaul estimated that Alger had spent between $12,000 - $15,000 on the families and kids for Christmas 1887, some $400,000 - $500,000 in 2025 dollars.

Word also had leaked out as to who their benefactor was. The Detroit Free Press carried back-to-back stories on December 29 and 30, 1887, about Alger’s philanthropy. The first compared him to Santa Claus and referenced “thousands of poor and unfortunate who are made glad by his bounty never speak his name except to couple it with a blessing.” It also noted that a large majority of family recipients were headed by “relief widows” and “deserted wives.” The second news piece detailed one families’ surprise upon taking delivery of the various gifts, and a newly outfitted newsboy advising his group was going to “draft resolutions of thanks to General Alger.”

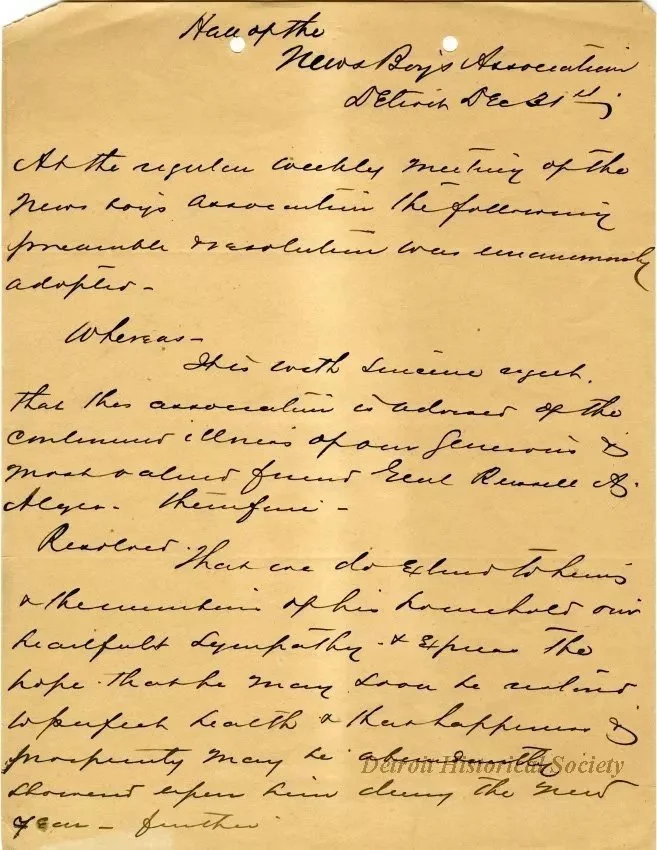

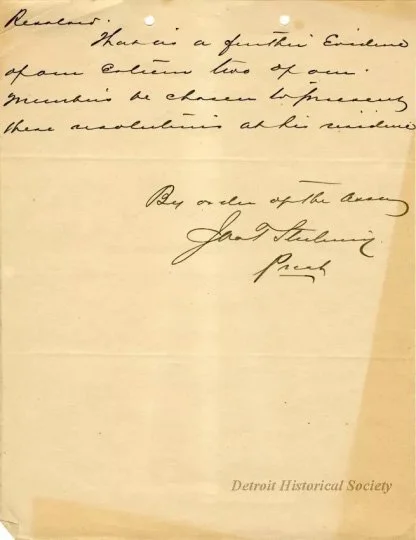

One of the many resolutions for General Alger. A typed transcript of the letter can be found at the bottom of the page.

The newsboys of Detroit benefitted from their newfound partnership with Gen. Alger, and he literally became their hero. He was mobbed by adoring newsboys whenever in public and serenaded with “What’s the matter with Alger? He’s all right!” If it was reported that Gen. Alger’s health was unwell, or when he suffered the death of his younger sister, Sybil, the newsboys would promptly respond with a public letter of good wishes or condolences for their friend.

Their relationship became particularly close after Alger attended the World’s Columbian Exposition (aka 1893 Chicago World’s Fair) several times and declared it “a valuable thing as an educator of the people.” He then paid for 14 private train cars to take between 600-700 of his newsboys from Detroit to Chicago and back to witness the Exposition for themselves. The lads had their once-in-a-lifetime adventure November 2, 1893.

The General continued his annual charitable clothing giveaway up until his death January 24,1907. At his massive Detroit funeral, his very lengthy funeral cortege consisted of 86 honorary pallbearers; the joint committee of the national House and Senate; state and national VIPs; three full bands; forty mounted police; the Corinthians’ and other Michigan Freemason groups’ members; 15 different military organizations’ members (GAR, Loyal Legion, et al.); and state, federal, and county officials. His beloved Newsboys’ Association, consisting of many hundreds of men (former Association members) and current newsboys, brought up the rear before the general public joined the solemn march.

James J. Brady was reportedly one of the original young newsboys helped by Gen. Alger’s kindness years before he started his Old Newsboy’s Goodfellow Fund in 1914.

After the General’s death, the Alger sons, Russell and Fred, kept their father’s tradition alive. At some point the complete suit of clothes turned into the presentation of a large check to the director of the Newsboys’ Association at a big Alger-sponsored Christmas bash. For years, the party was held in the garage of Russell Alger’s residence, The Moorings. The Alger family normally traveled a great deal but were always back in town long enough to host a grand Christmas party for the boys and bestow their check. Once the two sons died, the tradition was carried on for some years by their wives.

One long ago Christmas, Gen. Russell Alger tried to discreetly correct a situation he’d observed that he thought was wrong. Sometimes, the actions of one person that touches the “unseen” of society becomes lifechanging for thousands.

Credits: Newsboys’ resolutions letter courtesy of the Detroit Historical Museum.

Transcript of Resolution

Hall of the Newsboys’ Association

Detroit, December 31

At the regular weekly meeting of the Newsboys’ Association the following preamble resolution was unanimously adopted-

Whereas-

It’s with sincere respect that this Association is advised of the continued illness of our generous and most adored friend General Russell A. Alger. Therefore –

Resolved-

That we do extend to him on the unfortunate news* of his (word unknown), our heartfelt sympathy and express the hope that he may soon be restored* to perfect health and that happiness and prosperity may be abundantly showered upon him during the New Year ~ further

Resolved-

That as a further evidence of our esteem, two of our members be chosen to present these resolutions at his residence.

By order of the Assoc.,

James T. Sterling

Pres.

*editor’s interpretation of text, indecipherable handwriting