In Service to One’s Country

By Betsy Alexander

Service means many different things to people, the most obvious inferring being on active duty during wartime whether via inscription or voluntarily. Many patriotic Americans did not see battlefield action but did crucial work in other areas to contribute to the war effort. Others were born between conflicts, or were passed over for health, age, or other reasons so were turned down but wanted to serve. Still others worked with the government, service organizations, or veterans directly in an effort to assist the personnel who risked their lives for us and, frequently, returned with profound medical or other issues.

But a great number of service members didn’t return home at all. It is those men and women that are officially remembered one day each year that I address here: our KIA.

The Vietnam Veterans of America Chapter #528 (Plymouth-Canton, MI) contacted me for a project of theirs. They were creating a tribute, in the form of lamp post banners, to the seven service members from their community who died in Vietnam. They had sponsorships for three of the men already but needed additional information on the remaining four; two were particularly short on detail. I completed the first four members, then proceeded to dig into the remaining two.

Harry E. Baker, Jr. High School Photo

The first young man was 20-year-old U.S. Army SP4 Harry E. Baker, Jr., D Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Infantry, 11th Infantry Brigade, Americal Division, USARV. He was born in Grand Rapids, MI September 23, 1949, but moved to Mesa, AZ in 1960. The thing immediately noticed when viewing the few existing photos of Harry was that he looked very young in all of them even though they were taken at different ages. The photo shown here was on the occasion of his graduation from Mesa High School in 1967. Ironically, there were many baby-faced teens and young men who went off to war for us and didn’t make it home to their parents.

In 1966, his father, a master sergeant in World War II, passed away in a Phoenix VA hospital at the rather young age of 48. Nonetheless, Baker Jr. enlisted March of 1969 from Plymouth where he had moved following graduation; by October 17, 1969, he was in Vietnam. Five months later, on March 3, 1970, SP4 Baker was blown up while searching a booby-trapped VC shelter along the Trà Khúc River in Quảng Ngãi Province, South Vietnam.

His funeral service was held back in Mesa. He left behind his widowed mother, Julie, who died barely a year later at 53 years old, and his sister, Denise. SP4 Harry E. Baker, Jr. was the only one of the seven Plymouth men buried at Arlington National Cemetery where he rests alongside MSG Harry E. Baker, his father. (INSERT PHOTOS 2 & 3 - HEADSTONES)

Arlington Headstone of MSG Harry E. Baker

Arlington Headstone of SP4 Harry E. Baker, Jr.

“Butch” Sarah Playing Basketball

The other service member requiring more investigation was 24-year-old U.S. Army SP4 Hugh “Butch” Henry Sarah, D Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division, USARV. The working class Sarah’s definitely weren’t rolling in money but their son, born in Plymouth August 5, 1945, displayed a load of athletic riches.

He was “built solid, like a tank” and excelled at various sports. He set a record in shot put that stood for some 50 years, ran track, played basketball, and was the captain of the football team at old Plymouth High School. His steady was Vickie McCuaig, friends since they were 12 years old, Plymouth High Prom Queen, and his future wife; they both graduated in 1965.

Butch with Future Wife Vickie McCuaig

Graduation Day

The promising fullback went for a short time to the University of Wyoming where he played on their team and studied science before transferring back to this area. He had missed Vickie and joined her at Eastern Michigan University, which they were attending when they married July 2, 1966. He graduated with a BS in Biology June of 1968 while she completed her MA in Special Education. A man with a wicked sense of humor and varied interests besides sports and science, he was also an avid cartoonist and poet. After graduation he did not immediately seek employment. Instead, he enlisted in the U.S. Army August 28, 1968, a few days after Phase III of the Tet Offensive commenced.

Leaving for the military

As a degreed scientist and published writer, Sarah was highly coveted as potential officer material. He and Kent Ronhovde, his “new best friend” from boot camp at Fort Dix, decided they would go the Officer Candidate School (OCS) route and take the somewhat safer leadership role over the much more dangerous one as an Army grunt. Although they came from polar opposite backgrounds, the two men developed a deep bond in basic together. Ronhovde, a young man from a privileged, private education upbringing stayed the course at OCS and became an Army intelligence officer. Sarah, however, reconsidered after a few weeks of officer training. At 24 years old, he thought he could better serve by being in the thick of things in Vietnam alongside the younger draftees.

Both men’s leadership would be on display less than a year later.

By July 18, 1969, Butch was on the ground in Nam. Several days earlier, the issue of LIFE magazine hit the newsstands which carried the cover piece “Faces of the American Dead in Vietnam: One Week’s Toll.” It featured the 242 GIs killed in just the previous week, shocking middle America into reality. He also knew that Vickie was due to have their first child around the last week of September and he wouldn’t be able to get home to be with her. He was plunged into serious combat action, and it was time to lead. He wasn’t an officer: he was just a terrified self-designated grunt who volunteered to walk point. He reportedly felt it was his responsibility to lead as older, but he also privately journaled that he suspected he might not make it out of Vietnam alive.

Around September 11, his number came up. SP4 Sarah was out front again during a ground combat mission near the river by LZ Ike when an explosive went off. He suffered numerous devastating injuries, including a lost arm, and lingered mortally wounded in a field hospital before finally dying September 23, 1969.

Five days later his son, Hugh Kent Sarah was born to Vickie back in Plymouth.

Newspaper clipping, Plymouth Eagle, 10/2/1969

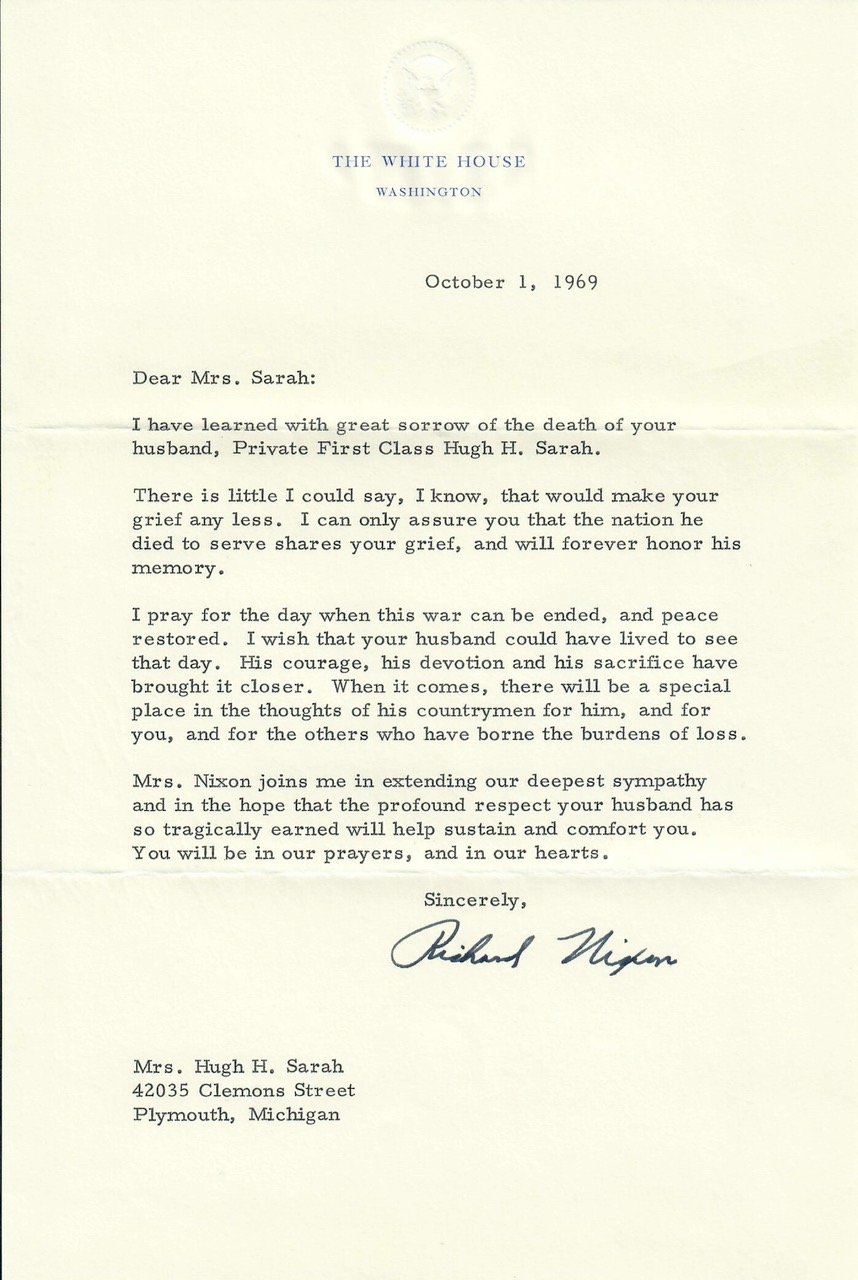

U.S. Army Captain Kent Ronhovde escorted his buddy’s casket back from Vietnam to Michigan per Vickie’s request and helped her plan and get through the funeral. She requested any monetary donations be sent to the Hugh Sarah Memorial Fund at Eastern Michigan University to enable their biology department to purchase new lab equipment for its students. On October 6, 1969, SP4 Hugh Henry Sarah’s service was held at the Schrader Funeral Home in Plymouth and his internment followed at Oakland Hills Memorial Gardens in Novi, MI.

Hugh Sarah’s headstone

Ronhovde continued to step up to aid Vickie and baby Hugh. He flew back and forth to Michigan to visit them, and they traveled to Washington, DC to spend time with him. Around six months after Hugh’s passing, Kent introduced his longtime friend, Kendall Wilson, to the Sarah’s. Kendall had a similar education and upbringing to Kent and was instantly smitten with the young widow and her baby. He very much wanted to take on the responsibility for helping them and pursued Vickie to move with little Hugh to her own place nearby his in DC. She agreed to marry him in 1974 just before Hugh turned four. Vickie had two more children with Kendall, obtained a second master’s degree, and worked in DC-area schools her entire career before retiring.

Kent Ronhovde’s A.B. degree cum laude from Harvard initially got him into OCS and Army intelligence. After his active-duty stint ended, he received his J.D. from Georgetown University and an MPA from American University. He parlayed this into a 36-year government career in senior management at the Congressional Research Service (CRS), as a legislative attorney and writer with the American Law Division, and was considered an astute counsel for Congress. He served his country well and in a variety of capacities before passing of pancreatic cancer February 19, 2010, in Washington DC at age 63. Kent left behind his wife, two daughters, and many friends in the U.S. government.

Kendall Wilson, or Ken as he was widely known, also led a long, distinguished life of service. He was two years older than Kent, and they both were graduates of St. Albans School. He went on to graduate from Princeton and MIT, an engineering whiz. Kendall served in Vietnam in the U.S. Navy before returning to Washington DC as a consultant, and to work at Pratt & Whitney aerospace, the U.S. Department of Transportation, and the U.S. Department of Energy. Kendall was appointed to serve on the FAA Management Advisory Committee by President Bill Clinton in 2000 and was on numerous boards of Washington non-profit organizations. It was noted that he “held a deep belief in service and community” and had a great “warmth and sincere desire to know and connect with people.” Last, it was said that “he would be remembered, above all, as an exceptionally kind soul.” This description sounds befitting of a man who realized that the infant of a newly widowed young wife would face an uphill battle without some significant intervention and kindness. Two brothers in arms stepped in to accept that onerous responsibility.

When I first located Hugh Wilson in early April, he had just returned from delivering his father, Kendall Wilson’s, eulogy at his Celebration of Life at Washington’s National Cathedral. Kendall had passed away January 18 of this year surrounded by his family and it was time to publicly speak of the man. Hugh only knew one father, Kendall, who made it clear from the onset that he was interested in, and loved, both Vickie and her baby son. Nothing could take the place of that love or change it.

Like Kendall, the younger Hugh was affluent and well educated at prep school followed by Duke University. He was a successful Wall Street banker in his 20s, but felt he didn’t “belong” and that something was missing; he chucked that live to study art. He received his MFA from the New York Academy of Art in 2004 and roamed obscure places around the world painting. But something was still niggling him.

What about Hugh Sarah, his biological father, who wanted to be a great scientist? What exactly happened in those seven weeks in Vietnam? Why were his death details so vague? Did he protect the younger guys? Did anyone else remember him or care when he died?

In 2015, Hugh embarked on his long journey in pursuit of the truth. First, he reached out to two of Hugh Sr.’s closest high school buddies, but they only had fun teenage stories about “the strongest guy,” “the hardest-hitting player,” and “the greatest guy they ever knew.” Nice, but that wasn’t what the son needed to know.

Master Sargeant Clyde Lee Bonnelycke

He next tracked down and phoned some of the surviving guys from Company D, aka the Angry Skipper Association, many who would not speak with him. However, one that did gave him the name of a key contact he needed to meet with. Hugh then flew to Lytle, Texas to talk to the one man who should know more detail: SP4 Sarah’s famous platoon leader, Master Sargeant Clyde Lee Bonnelycke, a genuine “Marine’s Marine” and a bit of a military legend.

For the uninitiated, “MSG B.” as he wished to be addressed, started out in the Marine Corps in 1958 where he spent 10 years and received a Silver Star for “conspicuous gallantry.” Shortly after his discharge he found himself bored with civilian life so he re-enlisted - this time with the U.S. Army. His assignment in Germany also bored him, so he groused about wanting more action until he was reassigned to Vietnam in 1969. He immediately racked up more awards for meritorious conduct through ambushes and heavy fighting - and SP4 Sarah was right there with him walking point for the next two of Bonnelycke’s Silver Stars. MSG B retired from the Army in May 1988, with three Silver Stars, four Bronze Stars, and two Purple Hearts between his Marine Corps and Army career. If SP4 Sarah was going to learn about service bravery and leadership, he was with the perfect mentor.

Bonnelycke spent the day retelling old war stories and gave some personal items to Hugh but stumbled recalling personal details about SP4 Sarah while he sorted through old documents and photos Hugh had brought with him. According to Hugh, this seemed to very much frustrate Bonnelycke as he knew this was one of his own men who was killed under his watch, and still he couldn’t remember much about him.

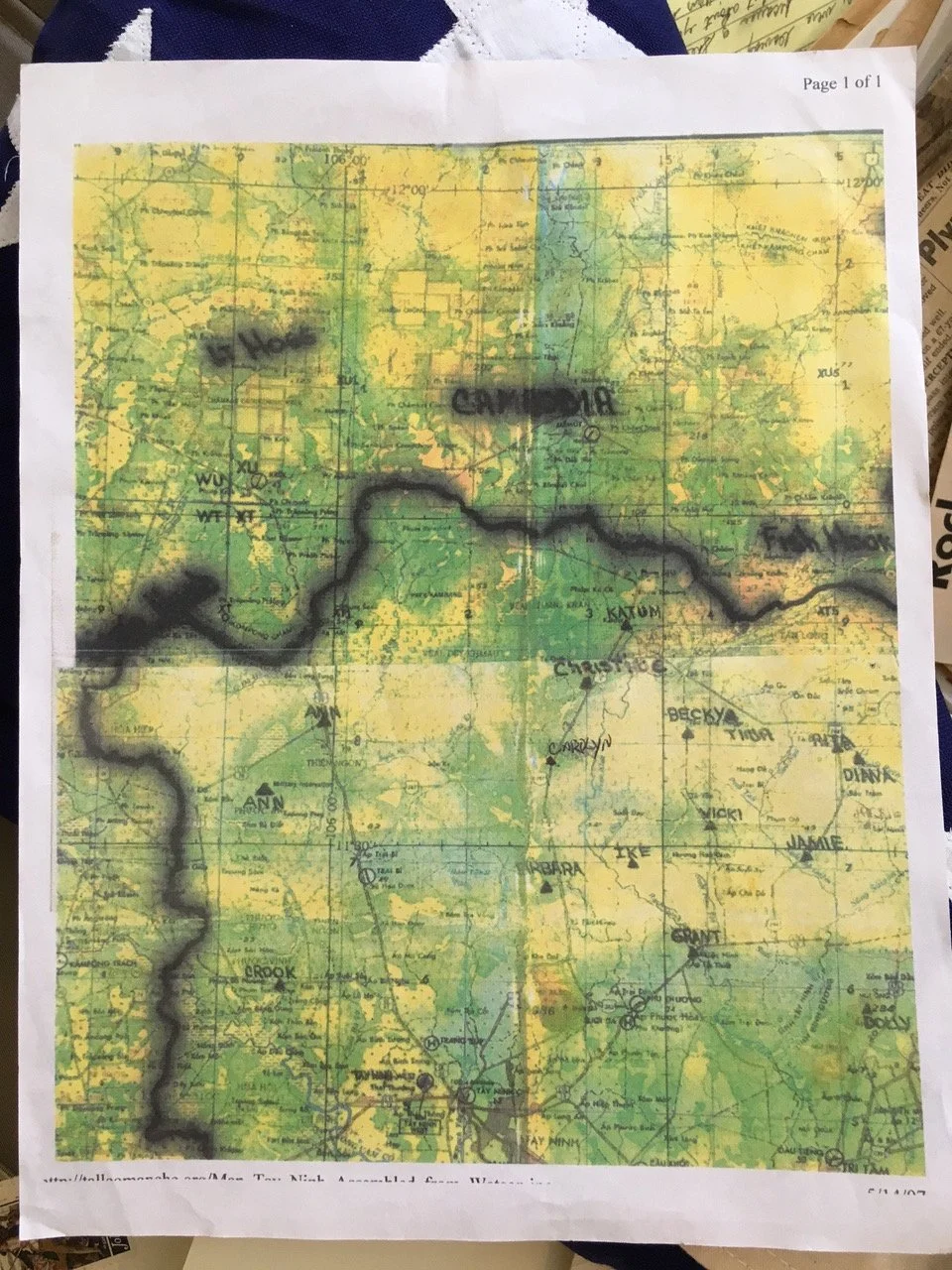

Map from the wall

Toward the end of Hugh’s visit, MSG B suddenly yanked an old, framed map off the wall and showed him a particular point. He declared, “Right here, this bend in the river. See it? That’s where the RPG hit that goddamn tree!” Now that was news. The family assumed that Sarah had stepped on an improvised explosive device (IED), and this new detail was not included in military paperwork. Now his platoon leader, who was on the spot when it happened, said otherwise very insistently and pointed out an exact location and how it happened on the map.

Clyde also 100% confirmed that the date of his father’s accident was not the same as his date of death, but that he had lingered for about 12 merciless days. Bonnelycke made a copy of the map for Hugh and the men parted ways. Whatever else they discussed from their day together was between the much-decorated CO and the son of one of his fallen men.

Several months later, Wilson attended an annual reunion of the Angry Skipper Association hoping for better luck a second time and in-person. He heard more colorful war stories, but again no one could recall SP4 Sarah or his death walking point for them. But one man, their second platoon sergeant, recalled hearing “the announcement of the birth of the dead man’s son.” The sergeant lost it and broke down in front of Hugh and the assembled Company D vets.

Why could no one actually remember this man who died leading them?

Still confused and with MSG B.’s map in hand Hugh Wilson set out for Vietnam, alone. He didn’t speak Vietnamese and didn’t exactly know his plan of attack; he just knew he had to go. He landed at Tân Sơn Nhất International Airport in the Ho Chi Minh City metro area on July 15, 2017, three days before Hugh Sarah had 48 years earlier. He ran into a local who spoke English and an old NVA veteran who gave him the lay of the land, then set out through Chu Chi just as the Company D guys had back in ‘69.

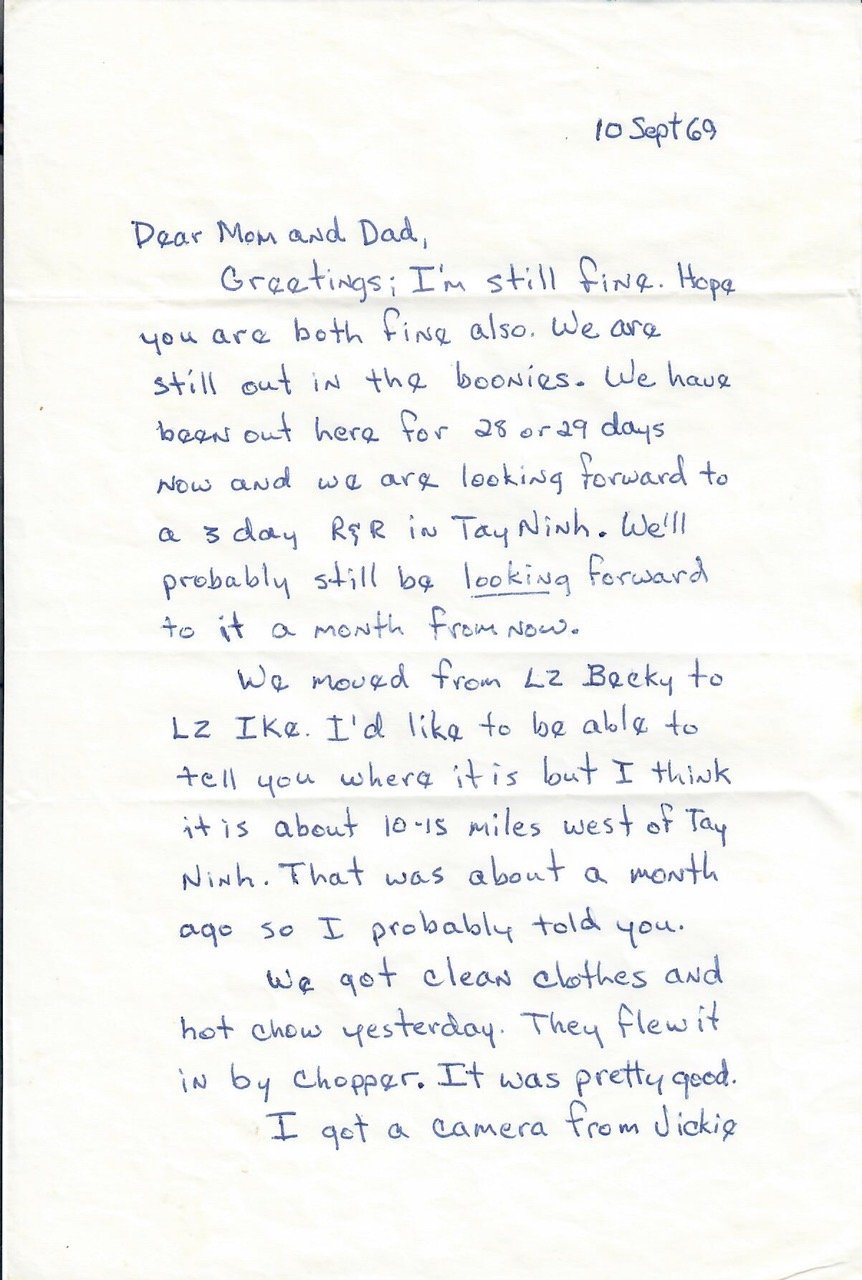

The faded 1960’s map and markers still held up remarkably well in 2017. As Hugh followed the stops on the map according to the directions Bonnelycke had given him he described that he was “facing his father’s ghost” by retracing the movements of his final days. Hugh Sarah had written home September 10, 1969, about having moved base from LZ Becky to LZ Ike and wondered when he’d ever get three days of R&R again in Tây Ninh. His folks and Vickie received that letter just after his death.

Hugh Sarah’s final letter home

Location of fatal wound

At Tây Ninh, he enlisted a young local named “Minh” as his driver. As they drove for about 45 minutes the river eventually appeared followed by LZ Ike, where Sarah had bunked down his last night. Just north of Ike, the narrow path turned down to the water and the bend, with jungle beyond, appeared where his father was mortally wounded.

As he walked around the peaceful spot, Hugh Wilson finally found some clarity. Although he carried the same name, he was suddenly aware that Hugh Sarah “was not a part of me, but separate and distinct. He was both my father and not my father; a hero to some and a forgettable man to others.” Ultimately came the simple realization that “he was a young man who never had a chance to fulfil his dreams.”

SP4 Sarah had enlisted in the service and taken a most dangerous position instead of choosing the easier path he was entitled to and ultimately died for his country.

Hugh Wilson continued to be a citizen of the world after his epiphany at the river bend. He traveled the globe painting portraits of locals and lived among various peoples to better understand them. After Vietnam, he finally no longer felt the responsibility to be exactly like his biological father or wonder if he would have somehow been a disappointment to him. He paid homage to him with the HHS Foundation and the Hugh Sarah Poetry Competition for incarcerated youths.

SG Clyde Lee Bonnelycke headstone

Vietnam War hero, MSG Clyde Lee Bonnelycke passed away in Lytle, TX on November 16, 2024, and was buried at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery.

When we honor those men and women who were killed in action, whether it be on Memorial Day or preferably every day, we might also consider the people in their orbit. Our many thousands of Harry Baker’s and Hugh Sarah’s left families and friends who all lost much more than their loved ones. Many of those affected by their loss were compelled to likewise step up and provided their own manner of service, as two men did so remarkably in Hugh Sarah’s absence.

Letter from President Nixon

Credits: Thank you to Gary Estermyer (Vietnam Veterans of America, Chapter 528); LIFE magazine; Meredith (Oakland Hills Memorial Gardens); Plymouth Eagle newspaper; and to Hugh Kent (Sarah) Wilson, for his family photos and personal recollections.

Also, thank you to SP4 Harry E. Baker, Jr., SP4 Hugh Henry Sarah, and the many thousands of men and women who gave their lives in service to the United States.